“If she was about to give life-changingly horrible news, she wouldn’t be in a good mood right now,” Sonia remembers thinking. In the waiting room, she glimpsed the genetic counselor laughing. On the morning she was to learn the outcome of her test, Sonia found herself clinging to superstition. The trip became a physical instantiation of their mental state: alone in a strange place, speaking only to each other. They never got over the jet lag and spent their nights wandering down side streets. The results wouldn’t come in for two months, so she and Eric went on their long-postponed honeymoon in Tokyo. It took weeks, but Sonia finally secured a test. What you can’t adapt to is something that keeps changing shape on you.” “You really want to hope that you’re negative, but the fear that you’re positive keeps interrupting, and it’s a constant psychological dialog,” she says. If a disease has no cure, their reasoning went, what’s the point in knowing? Isn’t ignorance bliss? But Sonia was adamant. Her doctors, genetic counselors, and even some of her family members recommended against it. Sign up for the Daily newsletter and never miss the best of WIRED.Īlmost immediately, Sonia decided that she wanted to be tested for her mother’s mutation.

“She wasn’t scared so much as sad,” Sonia remembers. Sonia, who was 25 at the time and living in Boston, called her mother often and visited whenever she could. She had trouble sleeping and spent her rare moments of lucidity grieving for the burden she had placed on her family. By May, she couldn’t eat, stand, or bathe herself.

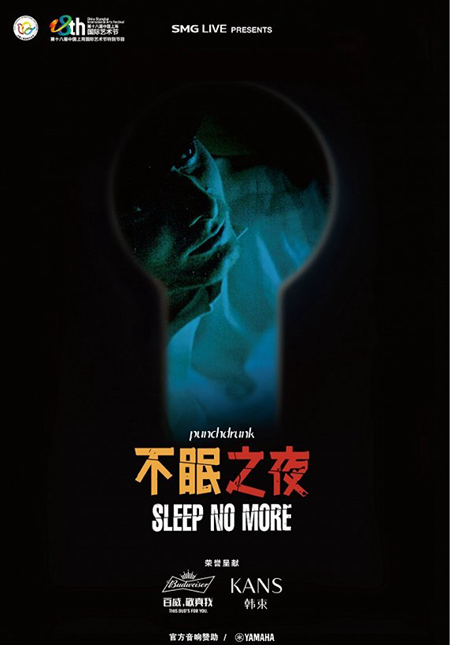

Sleep no more tv#

She was distractible, easily confused when she misplaced the TV remote, she’d look for it in the pantry. Once a poet, Kamni could barely string a sentence together. But by her birthday, that March, it was clear that something was seriously wrong. She’d single-handedly organized her daughter Sonia’s wedding, 300 guests drinking and dancing in the family’s backyard in Hermitage, a tight-knit former steel town. The previous summer, Kamni had been in good health. Maybe the harsh western Pennsylvania winter-two record-breaking blizzards in as many weeks-was wearing her down. She was 51 maybe middle age was catching up with her. But in early 2010, when Kamni Vallabh first began to complain that her eyesight was failing, there didn’t seem to be much cause for concern. In retrospect, it might have been a clue.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)